January 13, 2004

Susano-o in Drag?

It is my theory that the dancing Amenouzume (Heavenly-Alarming-Female) was in fact Susano in drag. In probably the most famous sequence in Japanese myth Amenouzume performs a strip tease dance on top of an over-turned barrel. This has the effect of making the assembled gods laugh. Amaterasu who is hiding in a cave, hears the laughter outside and thinks, gThis isnft right. They should not be laughing with me hidden in here.h So the sun goddess opens the door to the cave a little and asks, gHow come you are all laughing.h At which point a god replies, gsomeone as beautiful as you is with is,h and shows her a mirror. Seeing the mirror Amaterasu thinks that there is indeed another god as beautiful as herself outside and opens the door to the cave a little further, a which point a very strong god drags her out all the way, and another strings shimenawa behind her so that she cannot go back in. The evidence to support the theory that Amenouzume is Susano-o in drag is as follows:

1) Susano-o is absent from this portion of the myth even though he was the culprit. It was he that upset Amaterasu to the point were she went into the cave in the first place. It seems appropriate, therefore, that he should do something about it. 2) The dance raise such *laughter* when normally when real women strip tease the reaction is more of saliva, panting, and stares. In the Kojiki real-female nakedness is often regarded as being scary. So why did all the gods laugh? Perhaps they were laughing at Susano-o 3) Amenouzume "pulling out the nipples of her breasts." This seems to be a rather un natural action for anyone to do but it might be explained if one imagines a man doing a comic impersonation of a naked woman. 4) Amenouzume pulls her clothes down to her private parts, but does not seem to take them off entirely. Perhaps because if she had pulled here clothes down all the way she would have given the game away that she was really a man. 5) Amenouzume is the origin of Kagura - Shinto dance and later Noh that developed out of Kagura. And Kagura figures Susano-o prominently since it is of the Izumo region. 6) I saw a Kagura (sacred folk Shinto dance) rendition of this myth where the dancers were male. No surprises here since all the dancers are male but it drew a laugh from the assembled watchers precisely because of the fact that it was a man doing the "sexy" strip tease. 7) The sun goddess was definitely tricked here. She was tricked into thinking that there was someone else as beautiful as she outside. As mentioned in my article about hair, trickery in the Kojiki often seem to revolve around cross dressing. 8) Amaterasu may be *in a sense* the refection of Susano-o, as I will argue in a later post. So it seems appropriate that Susano-o should pretend to be her, as Amenouzume. It is clear that Amenouzume is pretending to be the sun goddess since the gods say that "there is someone as beautiful as you out here" before showing the sun goddess the mirror. The biggest problem with this theory is that Amenouzume is seen later in the myth. She is the god that escorts Sarutahiko to Izumo and is said to be one of the ancestors of the Saruta tribe.

January 12, 2004

Hair in the Kojiki

The Kojiki is famous for having themes that repeat over the course of its many episodes making it particularly tractable to structural analysis. As an illustration of this I will look at the way in which hair recurs as a repeating theme, with a similar function at several places in the Kojiki myth (here in the original Japanese)

In the first episode featuring Izanagi (male inviter) and Izanami (female inviter), Izanami dies and goes down into the underworld. Stricken with grief Izanagi visits his dead bride in the underworld and asks her to come back to the word of the living with him. She tells him to wait, and not to look at her. But Izanagi tires of waiting and in order to see Izanami in the darkness of underworld he breaks off a gmanlyh (i.e. end) tooth of the comb in his hair and sets fire to it.

When Izanagi is fleeing from Izanami he takes combs from his hair and throws them down, letting them turn to food, bamboo-sprouts, that his pursuers devour. There are similar myths were pursued people throw things down to turn into food to slow their pursuers all over the world. Why I know not, but as we see below, it will not be the last time that hair, or a head dress is used to trick someone in the Kojiki myth.

When Amaterasu waits for Susano-o, thinking that he may have come to steal her country, she dresses up as a warrior puts her hair in braids glike a man.h

When Amaterasu hides in the cave and throws the world into darkness, Amenouzume wears a fancy head dress in her hair when she dances before the cave in order to try and get Amaterasu to come out. The fancy golden head dress worn by shrine nuns (miko) when they perform Kagura (dance) today is based on the head dress worn by Amenouzume.

When Susano-o is banished from the high plain of heaven for upsetting Amaterasu, and thus sending the world into eternal darkness, his hair is shaved and his nails are removed possibly as punishment, possibly as purification. Incidentally, the ancient Jews used to do this to captive women of other religions before marrying them apparently, since it was believed that this robbed them of their magic power.

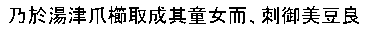

When Susano-o wants to kill the multi-headed snake Yamata-no-Orochi at a place called gbird hairh in Izumo, at he turns his bride to be into a comb and puts it in his hair. He then gets the serpent drunk and kills it in its sleep. That is the standard explanation. It is not clear why he turns his bride into a comb, nor is there any mention of how or when he turns her back into a person, except we learn in the next scene that he marries her. However, there is one rare reading, that I prefer, which has it that Susano turns *himself* into a likeness of his bride by putting a comb in his hair. The kanji in this sequence are

This is usually read as

Sunawachi, yutsutsu tsumakushi ni sono musume wo tori nashite mimidzura ni sashite

(Then, many toothed comb into that young womb took and turned {and} hairstyle into stuck)

But it might also be read as

Sunawachi, yutsutsu tsumakushi wo tori, sono musume ni natte, mimidzura ni sashite

(Then, many toothed comb took, that young woman into turned, {and} hairstyle into stuck)

This is the more natural reading since, there is no other place in the myth where a spirit is given the power of turning others into something else, and if he had that amount of power he would not have had to resort to getting the serpent drunk in order to subdue it. I also prefer this rare interpretation since it matches the story of Yamatotakeru, below. Later in the myth the soldiers of emperor Jinmu pretend to be party servers, possibly by pretending to be women. It seems to be a common way of killing ones foes in the Kojiki: pretend to be a woman, get them drunk, and then stab 'em!

The white rabbit of Inaba tricks some crocodiles into providing a bridge for him to get across some water by saying gWhy donft you all get in a line, and I will count which of your tribes is the greatest in number.h Just as he reaches the last crocodile he says, gHa, I tricked you,h thinking that his plan had worked, but the last crocodile bit him and tore his hair off. To add insult to injury some passing baddies tell him to go and bathe in salt water, which makes his skin crack and painful.

In the Hohoderi myth (in the Nihonshoki this is the myth of Yamasachiko and his brother Umisachihiko), sea creatures are defined as being those things that have fins, and land creatures are defined as those things that have hair.

The Great-Name-Possessor ties his host and father's hair to the rafters of a house to slow him down when he awakes.

When Yamatotakeru wants to kill some baddies he lets down his hair to pretend to be a woman and then kills the enemies in the midst of a party.

In the myth of emperor Jinmu his soldiers pretend to have cut their bowstrings under the pretence that they have given up the fight and then pull their bowstrings from their hair (again hair figures in a pretence).

As we can see, hair figures a quite a lot in the Kojiki and it is often associated with trickery and cross-dressing. Having long hair makes you strong in so far as it makes people look femininely attractive and thus able to trick and subdue their enemies.

Finally of all, it is worth mentioning that the Japanese for hair and the Japanese the deities in Shinto are homonyms - both "kami" (or "kami-no-ke" for more specifically hairs on your head). Kami is also the word for paper, the boss, government bureaucrats, and ones wife.

In real life the Japanese are very keen on their hair and very critical of baldness. Admittedly fewer Japanese go bald. Only about 10 or 20 percent, or perhaps half of the total in the West (I am guessing) but every day on television there is a range of adverts for wigs and hair lotions. To be a hage (a baldy) is second only to being dirty in terms of unpopularity with women. And alas, this author is quickly becoming bald.

January 11, 2004

Amae

I am told that Shusaku Endo, the Japanese Catholic novelist, sought a 'maternal Christ', believing that Japan as a land of 'amaeru' had a childlike dependence on a merciful compassionate mother. This notion, that the Japanese are inclined to amaeru, may ultimately derive, as Takeo Doi suggested, from a belief in humans as the children of kami and in particular Amaterasu.

Takeo Doi became famous with his classic book, The Anatomy of Dependence The title in Japanese is "Amae no Kouzou" ("The Structure of Amae") where Amae is the noun form of the verb "amaeru." The book is de rigeur for those that study the psychology of the Japanese, and highly respected academically. Doi's theory of Amae is quoted by most papers or books in this field. Doi has written several other books since and there are books about his theory written by other authors. For example, Susumu Yamaguchi of Tokyo Unviersity and x-head of a leading cultural psychology conference in Asia, started his research life investigating amae(ru) using questionnaires and or perhaps experiments. Osamu Kitayama, x-popstar and well known Japanese psychologist has edited a book of psycho-clinical papers on amae. All in all, amae(ru) is considered to be a critical, key word when attempting to explain Japanese culture.

Amae(ru) is according to Dr. Takeo Doi a word that cannot be directly translated into English. Doi starts out by making a Sapir-Whorf hypothesis based observation that any word that exists in one language but cannot be expressed easily in others, refers to a phenomena which is culturally important in culture of the first language, but not so important in the culture of the others which lack a means of its expression.

It is very true that Amae(ru) does not translate well into English. I would use "(to) fawn upon" or perhaps "to be a baby," or "to be cute." It refers to the action and emotional state of mind of a baby towards its mother (care giver). By "emotional state" I mean that it involves the expectation, need or desire to evoke the love in the other. Another way of putting amae(ru) is "passive love" i.e. feeling and behaving in such a way as to be loved (by a parent). It does not refer to being sexy, flirting or pouting or all the other ways of attracting eros (i.e. being "erotic" ?) but ways of attracting what C.S. Lewis calls "affection," the love of parents towards children. So amae is anticipating, and behaving in such a way as to receive love, affection, or induldence. The last word is moot too since the active form of amae in Japanese, amayakasu is usually traslated as "to indulge". One of Doi's most accessible examples is the behaviour of a puppy. A puppy (or an older dog, since dogs are always children to their masters) might roll on its back and wait for its belly to be stroked. Or it might come up to you wagging not only its tail, panting, and looking you in the eye. This is partly just being happy to see you but it is also a call for affection.

On top of the fact that Doi's insight regardign Amae started from a Sapir-Whorfian insight, it has a yet stronger relationship with language, or rather the lack of language. This connection can be approached in two ways.

First of all Doi's first, and for me most memorable, example of amae, is from when he arrived in the USA and visited a friend. His friend put some cookies or something on a table and said "If you are hungry, please help yourself." Coming from the culture of "amae," Doi felt put out. He was hungry, but he was in an amae frame of mind. He did not want to say, "Well I don't mind if I do," and tuck into the cookies. He wanted his host to actively perceive ("sasshi") that he was hungry and give him a plate of cookies. He wanted to be mollycoddled. The word "mollycoddle," not so common in English, helps us to understand the term amae. Some one who wants to be mollycoddled does not articulate their desire but hopes by their person or their actions to elicit indulgence from an other without the use of language. As soon as they put their desire into language they are putting themselves on an equal footing, as another separate desiring individual - but the person who "amaes" (if I am allowed to conjugate the verb) wants to merge (Doi argues) with the other.

This brings us on to the second connection between amae and the absence of language. Doi, argues that amae is the desire to merge with the other, as if (?) still not an independent entity, and puts forward a theory of individuality (quite common these days among narrative psychologists) that says that being an individual is to linguistically articulate oneself and ones desires. To amae is to refuse to go down that path to linguistic self-hood.

Endo Shusaku is possibly Japan's most famous Christian. Not only was he a Christian but also, as mentioned above, he tried to define a sort of Japanese Christianity. Indeed, Endo Shusaku attempted to take the best of Christian and Japanese culture to propose a more Japanese, and in a sense an even more Christian version of Christianity! In perhaps his most famous book ("Silence") Endo Shusaku raised the question of the martyr, the person that sacrifices themselves for others. The Christian bible tells us, "There is no greater love than this, that a man lay down his life for his friend." However, Endo suggests that there is greater love. Endo seems to come to the conclusion that the ultimate "martyr" could and would lay down his life for another, but ultimately she would also refrain for doing so, even if it meant rejecting all that she had lived for, if she felt that she would be held as an example, and thus encourage friends to lay down their lives as well. Putting it as tritely as this does not do service to Endo's sentiment but, Endo argues (successfully judging by the rave reviews from Western Catholics at Amazon.com) that sometimes it is even more difficult to *live on*.

Living on, even when this means not being entirely true to ones beliefs, is close to the philosophy of the Bodhisattva, such as. Kannon. A Bodhisattva is someone that could throw off their ego and reach nirvana/satori but decides to hang around, at the brink of satori, in the hope, working towards the day when, all other sentient beings reach nirvana/satori too.

It also reminds me of "About Schmidt" a film I saw today, in which the hero, played by Jack Nicholson, doesn't say what he really thinks, what he really believes, but chooses a polite, positive *silence* for the sake of those that he loves (perhaps a controversial reading of this bleak, but real and interesting film.)

Putting Endo's question back in terms of a possibly non PC gender related question: "who loves more, the fathers that go to war -- perhaps to die -- to protect those they loves, or the mothers that refuses to go to war, and would rather live in slavery, and abjection, for the same reason?" I think that opinions are likely to be divided. I am afraid that my sentiment is on the side of the warrior, but one might argue that a true blue Shinto-ist would come out on the side of the mother.

Shusaku Endo is a very famous novelist. His books are even more popular among Japanese Christians, who make up less than 1% of Japanese Christians.

Takeo Doi is also, as far as I am aware, a Japanese Christian. It is concievable therefore, in my opinion, that Takeo Doi may have been in part, subliminally inspired by the novels of Shusaku Endo. This is however, highly unlikely since (as kindly pointed out by Maraku below) Doi makes no mention of Shusaku in Amae no Kouzou. Takeo Doi does however, suggest, in the first chapter of his seminal work, that the origin of the word amae may be related to the name of the deity at the top of the Japanese panthenon, Amaterasu Oomikami. This suggests to me a common sensitivity motivating Shusaku Endo's and Takeo Doi's realisation that Japan is a country of amae. To Japanese Christians as they both are, it may be striking that there is a strong difference between their own religion, as expressed in the Bible, and that of the majority of Japanese who are much more enclined to amaeru to, request indulgence of, their deities.

Thanks to VikingSlav for the first paragraph and inspiration for this article.

N.B.

I would like to apologize for an earlier version of this article that suggested a closer link between the work of Shusaku Endo and Takeo Doi. This suggestion was entirely my own and based entirely upon supposition and speculation. In any event, nothing can be taken from Takeo Doi's immense achievement of making the notion of amae available to generations of psychologists, some of whom use the theory to cure people. And incidentally, academically, I am of course not fit to wipe Dr. Doi's shoes.

January 10, 2004

Women in Japanese Proverbs

There is a Japanese proverb which says (click for an image of the Japanese)

"Dawn doesn't break without a woman", or,

Japan is the land where dawn doesn't break without a woman. "

It refers to the Shinto myth in which the sun goddess, Amaterasu, hides in a cave and thus sends the world into eternal night, and means that Japan is the place where things don't go right unless there is a woman around. Thinking that perhaps the power of women might be expressed in Japanese proverbs I had a look around and came up with these:

One hair of a woman draws a great elephant

(or in the English tradition, more than a hundred yoke of oxen. )

Distant mountains move when wives speak.

But then looking on the Internet I found a paper on the subject in Japanese. There is also the famous book by Kitteridge Cherry

These argue, fairly convincingly, that Japanese proverbs about women tend to be damning. But at the same time they might testify to women's power.

For those that are interested in the position of women in Japanese (Shinto?) culture, here is as many as I could manage to translate.

Women's talk is limited to the village (that's all she knows)

Women's wisdom and a "red sky at night" are unreliable. (just as looking at the "Eastern" sky won't really tell you what tomorrow's weather will be, neither will there be anypoint in listening to the wisdom of women. It is about as reliable).

Women can't bow enough (or they should bow a lot, and ingratiate themselves)

Women's wisdom is as long as their nose (i.e. not very).

A bad wife is one hundred poor harvests (powerful but bad)

Don't show white teeth to a woman. Never smile at a woman. (or she will take advantage of you)

Wise women ruin cattle deals (because they are greedy, pushy, and loose sight of the big picture)

Women's wisdom arrives after the event (slow, & useless)

Women's strength and neckless stone Buddhas. (scarves are put on stone Buddhas, so neckless buddhas, and womenfs muscles are both useless. I think that this is referring to physical strength)

Don't be surprised by showing her arms or a morning shower. (both examples of slightly surprising, unsurprising things)

Women's bargains and numbers ending in 7 are not struck/dividable,

A bow drawn by a woman won't shoot (or hit the mark)

Women's eyes should be as big as bells (Men's should be as thin as twine).

Women's' toilet and ones circle of friends are best kept small.

Women should be flexible (and charming) in their dealings with people.

A Monk who takes offerings from the hand of a woman will be reborn as someone with 500 years without rest.

If you have three daughters your household will be bankrupt (because of their dowry).

Women fooling their husbands have more wisdom than men.

Women entering a room have 70 plots (Men entering a room have a lot of enemies.)

The tears of a courtesan (= crocodile tears).

Scared women and chilly cats are liars. (they are pretending)

The origin of women's wisdom is greed.

Women are messengers/angels of hell (and the downfall of many a man)

Even if you have seven children do not trust the heart of a woman.

Bad women pretend to be wise/kind

Women are wise in the ways of love.

Complaint is the way of woman

A woman's mouth never blooms (but says nasty things).

Women together lock horns.

A women's revenge is three times thick.

A women's resolve pierces stone.

Women's mind and autumn sky (A woman's mind and winter wind change often.)

Three women together make a din (the character for din is written using the character for woman thrice. Three women, and a goose, make a market.)

Women know the ways of women.

Women's minds are like cats eyes (roving, flitting all over).

Cold women and famish cats are sleight of hand.

Women are essentially water (changeable)

Women have 12 horns.

Icefish and women are not to be eaten after they breed (both are not tasty, apparently)

Jealous women will tell anything.

Women care about their clothes second to their lives.

Torii: Sacred Bird Gate

A torii is a gate with two overhead cross bars or lintels. Torii are found in front of almost every shrine in Japan. Their function is to mark the boundary between the sacred world of the shrine and the profane world outside. Shrines vary in size and design, some being over 25 metres tall and stretching over roadways. Others being just big enough to pass underneath. Indeed,. one theory to explain the etymology of the name suggests that it is related to the Japanese pass into "toori-iru."

There are several theories to explain the origin of the torii...

In front of the towers in India where the Buddha's relics are kept there is a gate resembling a torii called a Traana (sic). Since the word and the object both resemble the twin lintelled gate in Japan there is a theory that this Buddhist gate is the origin of the Shinto torii.

In front of Chinese palaces and tombs there are "kahyou" (japanese reading) which resemble torii. The Kanji for Kahyou are sometimes read as "torii" in Japan, and the same Kanji are used to describe the Japanese torii in China.

The Japanese had a long tradition of hanging shimenawa or rice straw rope between two poles. There is a theory that these "shime columns" were the origin of the torii.

When Amaterasu hid herself in the heavenly cave (ama no iwato) the other spirits arranged for the "eternal long crowing birds" (cockerels) to crow, which is one of the ways in which Amaterasu was convinced that dawn had arrived without her (that there was "another goddess as beautiful" as her). When she opened the door to the cave a little she was shown a mirror (which she presumably took for another god, but later she refers to it as herself, or her avatar on earth). Ceasing this opportunity, Amaterasu was dragged out of the cave to the relief of the assembled spirits. The place where the cockers perched may have been the origin of the torii. The use of cockerels crowing to fool supernatural things into thinking it is dawn is a theme common to other Japanese traditions.

Whether or not the torii relates to the above incident in the myth or not, since the characters used to represent torii are those of "a bird" and "to be," many interpret torii to mean a place where it is easy for birds to be and there is considerable evidence that torii have something to do with birds.

On at least two occasions in the Japanese creation (Kojiki) myth birds are messengers between the spirits and humans. In one episode a bird or bird-woman is sent by Amaterasu from heaven to Japan as a messenger. She ends up being shot through the heart with an arrow. In another, when the proto-samurai, warrior hero, Yamatotakeru dies his spirit is taken to heaven by doves. The function of birds as emissaries between spirits and humans suggests it is appropriate that they should "be" at the boundary between the sacred world of the shrine and the

profane world outside.

There is further evidence in that there are drawings in ancient Japanese tombs showing birds perched on torii-like structures, and there are wooden bird shaped items that were found at the ancient Oosaka prefectural government offices (Oosaka Fu) and at the top of and surrounding ancient tombs in Nara.

The Aka tribe of Northern Thailand have a tradition of erecting gates resembling Torii at the entrance to their villages, upon the lintels of which are placed wooden effigies of birds. The birds are said to watch out to prevent the entrance of evil spirits into the village.

Noh and Shinto

The spiritual roots of Noh lie in a much earlier tradition than Zen. They are evident in the Shinto-style stage and the back wall with its painted pine tree. This is thought to be a reference to the Yogo Pine at Nara's Kasuga Shrine, to which Kannami had been attached. One day an old man was seen dancing beneath the tree, who turned out to be the spirit of the shrine in human form. The legend tells of the essence of Noh and the bond between men and gods. Before the sacred pine, the ritual drama realises a magical moment of transformation when the spirit world stands revealed.

Dance as an offering to the gods has a long tradition in Shinto. It is said to have its origins with the goddess Uzume, who performed on a wooden tub, stamping her feet and exposing herself in ecstasy. This was because the sun-goddess, Amaterasu, had withdrawn within a cave, plunging the world into darkness. Uzume's dance provoked clapping and cheering from the onlookers, which made Amaterasu peep out to see what was happening. A mirror was held up to blind her with her own brilliance, and a rope slipped across the entrance to the cave to stop her going back in. Sunshine was restored.

The spiritual dimension of Noh is evident in the spurning of realism. The concern is not with the material world, but with spirits, lost souls, and the supernatural. Redemption, passion, recollection, and longing are the themes. The music is eerie, the movements unworldly, and the lead character masked. There is no scenery, and barely any props save for symbolic markers to indicate a gate or boat.

January 09, 2004

Holy Sake : Rice Wine & Shinto

Rearding the position of sake in Shinto, it seems as if the two are inseperable. Jichinsai: Sake is along with salt and water used for purification, particularly since spooshing it about placates the spirits. The stable bread and butter work of many shrine priests today is the jichinsai or "ground pacification ritual" that is carried out prior to the construction of any form of building. In the jijinsai a liberal amount of sake is spread upon the ground. Similarly sake is poured into water to pacify the gods of the sea and rivers by fishermen. Here is A ground purification festival in pictures. in particularly please see jitin9.jpg for the sake and tamakuji at a ground purification festival oToso a sort of medicinial sake

is a traditional drink on the third day (or first) of the new year. I have seen many a Japanese family drink sake but originally and properly "oToso" is a herbal medicinal alcohol originally imported from China. It first became a New Year's Tradition in the reign of emperor Saga in the Heian Period. Omiki is the name of the holy sake that one can imbibe when one visits a shrine. It is also put into the Heiji - white lidded bottles -- on the Kamidana. This very pleasant Japanese site shows food at shinto festivals, the first being sake, and this is my page, now old. Omiki, or the ingredient thereof (as yet un holy sake) is also a popular thing to give to shrines and barrells of sake will be seen on display at most shrines. Kagamibiraki (mirror breaking or unveiling) is the tradition of breaking open the top of a barrel of sake when something auspicious happens. The mirror that is unveiled in this case is presumably the surface of the fluid. Kagami biraki originally refered to the breaking open or taking down of the round rice cakes that are put on display over new year. Please see the last photo on this page for some people doing Kagami biraki on some Gekkeikan sake Sansankudo (three three nine) is the process by which the bride and groom in a Shinto Marriage ceremony take three sips to drain three shallow cups of sake, to ceal their marital vows. I have thought that the wideness of the cups is to provide a reflective surface so that as well as drinking sake one is also drinking a reflection, possibly of oneself and ones bride. (see this photo of Tsukimizake) Amazake: (sweet sake) The partically fermented "oatmeal" rice paste gruel that is traditionally served at some Shinto festivals and shrines. There is festival somewhere in Kyuushuu where it traditional to sit down and paste this over each others faces, while imbibing some of the finished product. Kadomatsu (gate pines) I have a personal theory that the acutely sliced, pointed bamboo poles, with a little pine added for good measure, are in fact sake cups. This is because I have had the experience of drinking warmed sake from items almost identical at Shinto festivals. I have not seen this argued eslewhere, but if one had a large appetite for sake, it would be possible to use Kadomatsu in this way. Please see the photos of cut green bamboo poles. Tsukimisake (moon watching sake) The tradition of drinking sake in which the moon is reflected at a moon watching (Tsukimi) festival. I have read that if maidens drink sake in which the moon is reflected they become pregnant. Here is a picture of the moon relected on a traditional sake bowl. While writing this mail I came accross this page all about sake traditions in Japan, in Japanese. There are plenty more sake customs than the ones I have outlined above.